My parents won the green card lottery. Did they, a middle-aged couple with a six-year-old, plan on uprooting their lives and coming to the U.S.? No.

Did they do it? Absolutely.

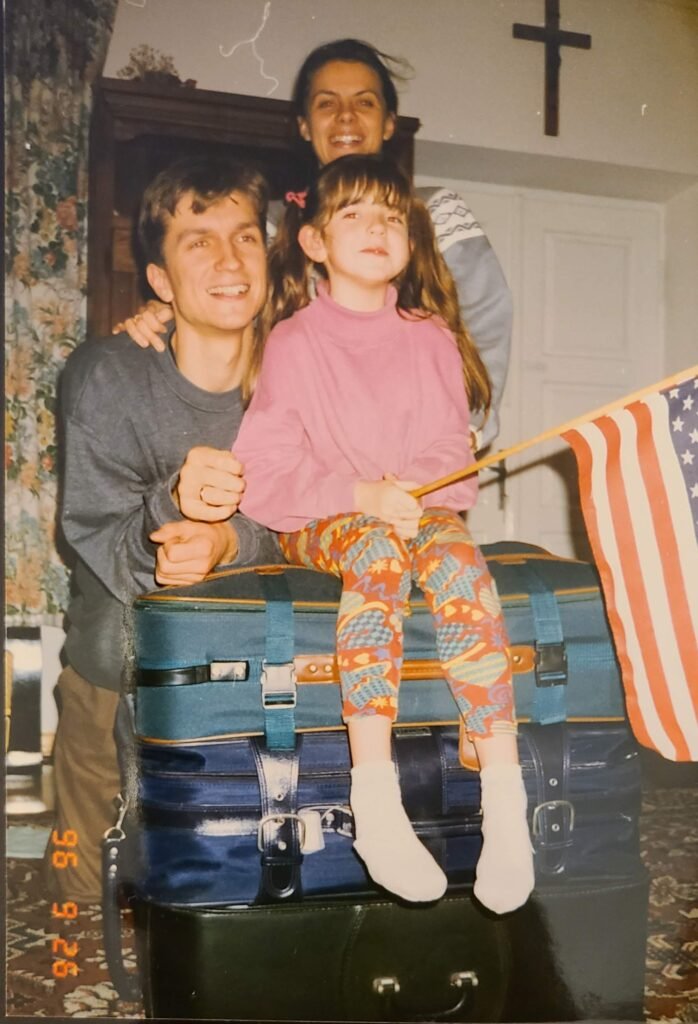

It was a dark September morning when I, a spindly six year old with pigtails, walked out the door for the last time as a permanent resident of the home—and country—I grew up in.

I knew what was going on (my parents didn’t spring up a transatlantic move on me last minute), but I didn’t understand the significance of it. At the time, I was more concerned with solving jigsaw puzzles, building sand castles, and pretending I was Sailor Moon.

But there we were, squeezing into our Big Fiat, embarking on a 5-hour drive to Warsaw along narrow, pothole-filled roads. The bumpy trip was a reminder of the decades-long Soviet occupation that had ended just a few years earlier.

Born in 1990, I didn’t know anything about life in socialist Poland. But my parents and older siblings knew it all too well. Rations for everything from shoes to gas to sugar; standing in long lines for a loaf of bread; the fear of speaking out against the government. Injustice in positions of power. Empty store shelves. Distrust. Censorship. Martial law.

Soviet control over Poland had ended in 1989, and with it had come a wave of hope: The rebirth of Poland. Still, my parents and I were on our way to catch a one-way flight to the United States. Why?

Even though things were improving, the country was still struggling. The economy would take several years to repair, and my family was just offered what they perceived to be the golden ticket to the promised land.

For many, this move may sound crazy. Two people in their 40’s, with zero knowledge of English, immigrating to a new world with a young child. It still sounds crazy to me. But at the time, the pull for a better life was powerful.

Seeking a better future

In a 2023 survey of immigrants, the majority, regardless of where they came from or how long they’d been in the U.S., said they moved to the United States in search of more opportunities for themselves and their children. These opportunities were in the form of education, work, and possibilities that they were not afforded in their home country. A vision so tempting that they decided to uproot their lives for the foreseeable future, leaving all that was familiar behind, heading towards potential but also uncertainty.

This was exactly what had attracted my parents. They were not doing poorly in Poland: they had jobs, a beautiful house and garden, and three grown children who had done well for themselves. But, in their minds, if they took a chance and worked hard enough, things could be even better.

Into the deep end

Not only did we move to a different country, we moved to a completely different environment. The airport itself was a nice introduction into life in New York City: a mass of people, different races and cultures, speaking different languages, hurrying along to their destinations.

From a rural Polish town to one of the largest cities in the world, the change in scenery was drastic. Gone was our large garden full of vegetables, fruit, and flowers. Gone was the sound of crickets and trees rustling in the wind at dusk. Instead, the window of our shared apartment looked out onto a sea of houses surrounded by drab concrete sidewalks. Whining ambulances and car alarms replaced the chirping crickets.

It was a shock, for sure, but the adjustment must have been tougher for my parents, who were more accustomed to a certain way of life. As a 6 year old, I hadn’t yet experienced much of life, and certainly didn’t remember most of it. In that way, it was easier to see this bustling, colorful place as a new normal.

Because my brain was still readily absorbing information, I learned English in about 6 months. Prior to that, I remember being very confused as to why no one could understand me (and vice versa). I was bullied, as kids make fun of me and stole various school supplies that I’d brought from Poland. I didn’t understand why they did it—I hadn’t done anything to them. I was just different, and therefore vulnerable. More surprising than the students were teachers who accused me of stealing, knowing full well I could not defend myself.

Still, there were many individuals who did the exact opposite, showing kindness and understanding. From family friends who drove us from the airport or helped enroll me in school, to my first grade teacher who took me by the hand and assured me I would be okay—there were so many helpers who made us feel less alone in our new, and very different, home.

Did I do the right thing?

For many individuals, including my parents, such a move like this is followed by years of questioning:

- Did they make the right move?

- Did they unnecessarily separate the family, alienating us from each other?

- Could I have had an equally good life in my home country?

I reassured them: no, I would not have.

Of course, I don’t actually know. We seldom know what “could have” been. But I do know that I am thankful for all that I’ve had the opportunity to experience so far.

I am grateful for my parents decision to move, and in awe of their bravery. With no internet or smartphones and a limited knowledge of English, to leave behind one’s home for the possibility of a better future for the entire family, was a little crazy and a lot bold. Even more impressive is their awareness that they would likely not see the fruits of their labor firsthand—their choice would primarily impact their children and future generations.

I am eager to share my stories in future posts, but would also love to hear yours. If you are comfortable with sharing your experiences as an immigrant, please leave a comment below!